Any drug that makes it to this step will have already made it past phase 1, meaning it has already undergone sufficient development. Phase 2 and phase 3 trials need to be registered at the government’s clinical trials website as required by 42 CFR part 11.

That being said, there are important details to consider when developing best practices for COVID drug trials, including population selection, trial design, efficacy endpoints, safety considerations, and statistical considerations.

Let’s dive in.

Best Practices for Population Selection

First thing’s first – you need to consider who you’ll be testing, and the FDA makes a number of recommendations concerning population selection for preventative and treatment trials.

Range and Diversity

Any trial needs to consider a wide range of people with different risk categories, ethnicities, locations, and ages. For drug trials specific to COVID treatments, the FDA suggests a range of people including outpatient, inpatient, or inpatient on ventilators. Ensure that you also include people at high-risk due to underlying conditions and age. Examples include those with heart disease, diabetes, HIV, or cancer.

If appropriate, the FDA also encourages pregnant people to enroll in phase 3 trials. And, if there’s a specific benefit, children can also be enrolled.

The FDA also recommends that testing sites be flexible. Consider opening new sites or suspending old ones in accordance with fluctuations in infection frequency.

Prevention trials

Trials intended to test preventative drugs should be conducted in communities with confirmed, well-documented cases. Pre-exposure trials include high-risk individuals showing no symptoms, like nurses, doctors, and first responders. Post-exposure trials include people with no symptoms who have documented exposure to a probable or confirmed case.

Treatment Trials

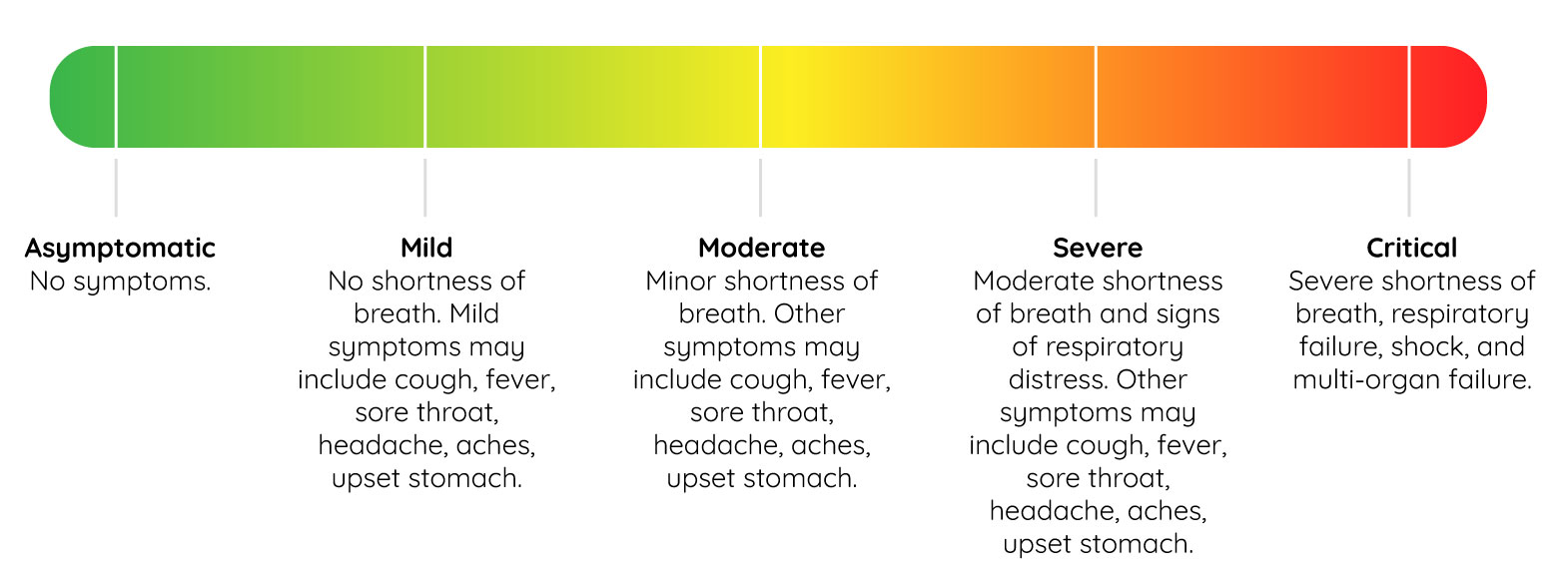

The FDA advices that treatment trials should include those with laboratory confirmed cases of COVID-19. Prior to starting, a baseline for the severity of symptoms should be objectively set. If you need guidance concerning severity criteria, here’s a helpful graphic that outlines COVID case severity:

Best Practices for Design

You’ll need to test the drug in “randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trials using a superiority design”. Of course, keep your standard of care in all treatments and let people know if you will use off-label drugs, devices, or interventions.

It may be beneficial to design a trial with a smaller population. Then, if there is solid preclinical or preliminary evidence for success, expand the trial to a larger population.

According to the FDA, a 4-week duration is likely enough time to capture the most important data for ventilated patients, while a shorter duration might be appropriate for those are are less ill.

Events that occur outside of a current trial which may motivate revisions to its design should be considered and discussed with the FDA. Talk to the appropriate clinical division to best understand the standard of care, especially if a treatment has become standard for a specific population like severely-ill hospital patients.

In certain situations, it might be appropriate to perform decentralized or platform clinical trials. In this case, you must discuss your plans with the FDA.

Other high-level design guidelines for safety include:

- Limit in-person contact to reduce the risk of infection

- Use an independent data monitoring committee (DMC) for safety and integrity, and ensure that your charter is submitted as soon as possible

- Ensure you have an exit strategy. All trials should incorporate a plan to stop in the case of futility or harm. This plan should halt the trial if the drug is causing harm, and continue the trial if the drug is effective.

Best Practices for Determining Efficacy

Let’s face it. No matter what we do, any drug trial can be influenced by a variety of factors that are out of our control. In turn, this can influence the efficacy of testing. The FDA has several recommendations to counteract bias.

Evaluate the effects of the drug you’re testing against the placebo. After all, the effects may be influenced by the population, the clinical setting, or the baseline severity. Also be aware of important clinical outcome measures like all-cause mortality, respiratory failure, need for invasive ventilation, need for ICU care, need for hospitalization, and demonstrable improvement.

The duration of the trial should capture the important events for the entire progression, and the time point you choose should be defined as number of days after randomization. Keep in mind that population selection will probably influence the timeframe and “definition” of endpoints. Proactively record potential relapses in your endpoint definitions. For example, with severely-ill patients, appropriate endpoints could be:

- All-cause mortality after an appropriate amount of time (e.g. at least 28 days)

- Proportion of survivors after an appropriate amount of time (also at least 28 days)

- Time taken to move to sustained recovery after an appropriate amount of time

In prevention trials, the primary endpoint should be confirmation of the disease through a pre-specified point in time. It’s also important to evaluate cases with and without symptoms. Additionally, evaluate cases with patients receiving prophylaxis and patients who are not – symptoms of COVID-19 may be milder in those receiving it, so comparative hospitalization data is of interest to the FDA.

Best Practices for Ensuring Patient Safety

Analyzing the efficacy of new drugs on human populations always contains a level of risk. The FDA recommends a few safety considerations in trials related to COVID prevention and treatment to make them as safe as possible. Let’s take a look at the high-level recommendations.

- As we mentioned during the population section, include a broad population of people in well-controlled and well-performed trials. This will generate best practices for use if the drug is released.

- Construct a database to store and record information about the population tested, the treatment’s effect, the drug’s toxicity, and the experience the medical community has had with the drug.

- Provide a standardized toxicity scale for clinical trials with severely-ill patients. Examples of these scales have been published by the National Institutes of Health’s Division of AIDS and the National Cancer Institute (NCI).

- Consider potential drug interactions that could increase toxic risk and lay out mitigation strategies.

- Safety assessments should correspond with the severity of illness and the potential risk of the drug, such as vital signs, laboratory studies, and electrocardiograms.

- Conduct safety reporting from FDA regulations.

Best Practices for Statistical Analysis

Ultimately, analysis should be conducted in an intention-to-treat population – all randomized. This analysis should be specified in the protocol.

Also, size matters. Justify assumptions with calculations only in sample sizes that are large enough to provide reliable answers to safety questions the trial is addressing. Analytic approaches for primary efficacy analysis include:

- Binary outcome analysis: Each person is classified as having a successful or unsuccessful outcome

- Ordinal outcome analysis: A weight is assigned to each category or it is rank-based with analyses of how treatment impacts different categories

- Time-to-event analysis: Kaplan-Meier curves in each treatment group for log-rank tests

- To improve the accuracy and precision of treatment effect estimation, adjust for certain variables and propose different methods for each. Examples of these variables include age, baseline severity, underlying conditions, and more. If your population includes mixtures of severity, conduct subgroup analyses by severity to asses the efficacy of treatments.

Additionally, it’s important to minimize missing data. Distinguish between discontinuation and withdrawal from assessments, and encourage participants to stay in the study and conduct a follow-up.

Winning the Fight

With population, design, efficacy, safety, and stats considered and planned, our efforts will have some teeth in the fight against this virus.